The hidden ingredient in Rembrandt’s impasto

21 January 2019

Impasto is thick paint laid on the canvas in an amount that makes it stand from the surface. The relief of impasto increases the 3D perception of the paint by the differences in light reflection of the textural surface. Scientists know that Rembrandt achieved the impasto effect by using materials traditionally available on the 17thcentury Dutch colour market, namely lead white pigment (a mixture of hydrocerussite Pb3(CO3)2.(OH)2 and cerussite PbCO3), and organic mediums (mainly linseed oil). The precise recipe was, however, unknown until today.

An extremely rare component

In a scientific publication in the leading chemical science journal Angewandte Chemie, researchers from the Netherlands and France now describe that they have discovered another important component in the paint used for the impasto effect. This plumbonacrite (Pb5(CO3)3O(OH)2) is extremely rare in historic paint layers. It has been detected in some samples from 20th century paintings and in a degraded red lead pigment in a Van Gogh painting.

According to the researchers, its presence in Rembrandt's paintings is not accidental or due to contamination, but it is the alteration product of the particular paint prepared by Rembrandt.

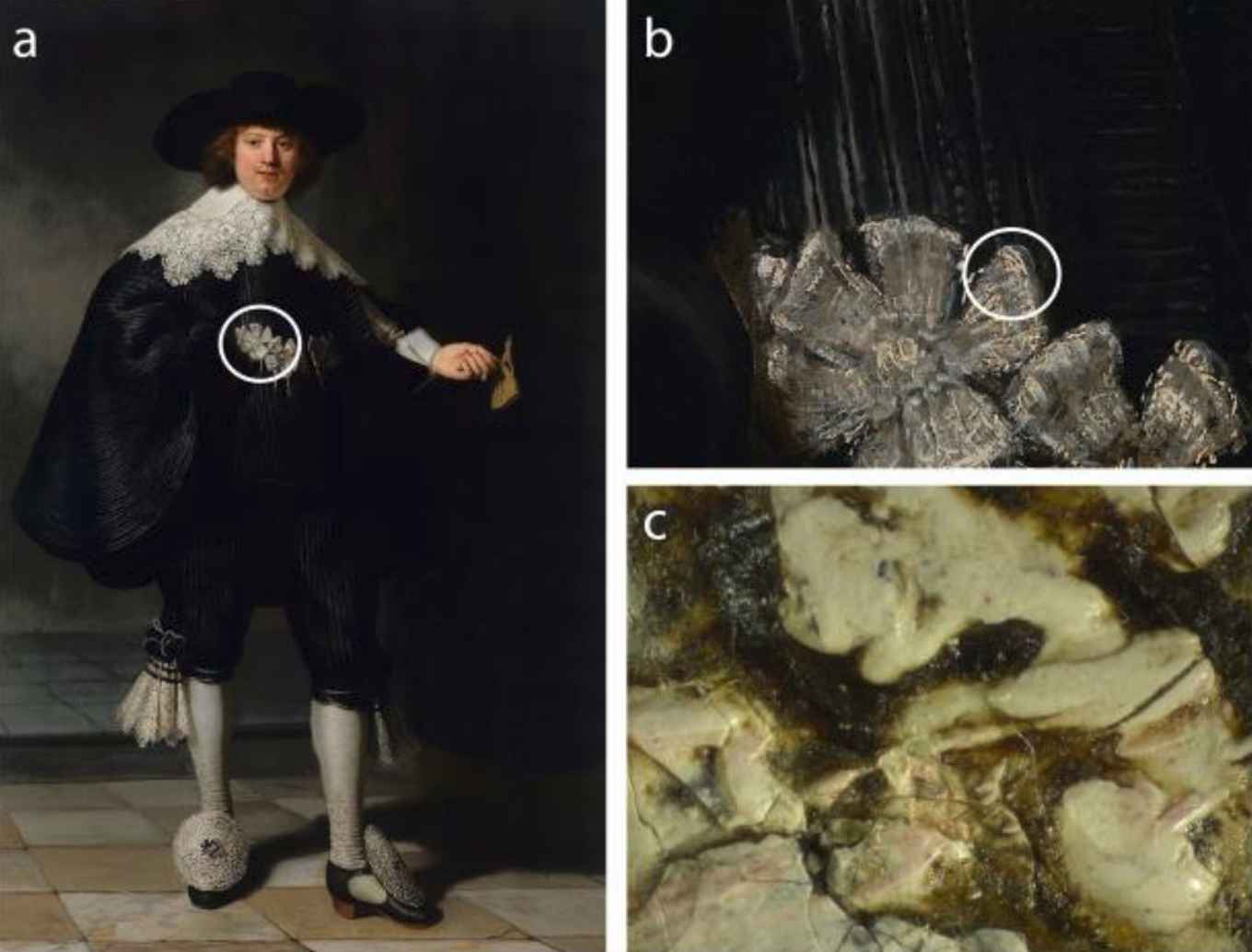

The team, led by Delft University of Technology and the Rijksmuseum, sampled tiny fragments from the Portrait of Marten Soolmans (Rijksmuseum), Bathsheba (The Louvre) and Susanna (Mauritshuis), three of Rembrandt’s masterpieces. These fragments, less than 0.1mm in size, were investigated using high energy X-rays at the European Synchotron Radiation Facility (ESRF). This yielded detailed information about the paint composition and thus the plumbonacrite was found.

Underlying mechanisms

Interpretation of the results was carried out in close collaboration with Dr Katrien Keune, researcher at the Rijksmuseum and associate professor at the Van 't Hoff Institute for Molecular Sciences (HIMS). At HIMS she investigates the chemical interaction between pigment and oil binder, and studies the chemical ageing and degradation of oil paints. The HIMS group is known worldwide for its knowledge of the behaviour of lead soaps and associated lead products in historic paintings. 'With our expertise we have contributed to the understanding of the mechanisms underlying the formation of plumbonacrite', says Keune. 'The composition and conditions of the aging lead-containing oil binder around the pigment play an important role. The exact underlying mechanisms are not yet fully known, but we will soon be conducting further research on that.' This entails, amongst others, the reconstruction of specific impasto-like samples and preparing and ageing them under different conditions.

Paste-like

The research has already made clear that Rembrandt modified his painting materials intentionally. The presence of plumbonacrite is indicative of an alkaline binding medium and based on historical texts the researchers believe that Rembrandt added lead oxide (litharge) to the oil. This resulted in a paste-like paint mixture. This knowledge will contribute to strategies for the long-term preservation and conservation of Rembrandt’s masterpieces.

To assess if lead white impastos systematically contain plumbonacrite, the number of samples studied is not extensive enough. 'We are working with the hypothesis that Rembrandt might have used other recipe', explains Annelies van Loon, scientist at the Rijksmuseum. 'That is the reason why we will be studying samples from other paintings by Rembrandt and other 17th Dutch Masters, including Vermeer, Hals, and painters belonging to Rembrandt’s circle'.

The research, led by the Materials Science and Engineering Department of the Delft University of Technology and the Rijksmuseum, is a collaboration between academia (Institut de Recherche de Chimie Paris, Sorbonne University and University of Amsterdam), Cultural Heritage research institutes (C2RMF: Centre de Recherche et des Restauration des Musées de France) and museums (Rijksmuseum and Mauritshuis).

Article

Victor Gonzalez, Marine Cotte, Gilles Wallez, Annelies van Loon, Wout de Nolf, Myriam Eveno, Katrien Keune, Petria Noble en Joris Dik: Rembrandt’s impasto deciphered via identification of unusual plumbonacrite by multi‐modal Synchrotron X‐ray Diffraction, Angewandte Chemie International Edition, online 7 januari 2019

DOI: 10.1002/anie.201813105

Press release of Delft University on this research:

The secret to Rembrandt’s impasto unveiled.